Prebiotics: what, how, why & which

The wonderful world of prebiotics. That banana should be less ripe though!

Introduction

Probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and now postbiotics. It’s a lot. There’s some science but also a lot of froth, so how can we navigate this terrain? Here we discuss prebiotics and synbiotics, with probiotics and postbiotics to come. Thank you to Julia for this question.

To set the scene, here are the different actors:

| What | Definition | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Prebiotic | Food for the microbiome. Undigestible by people, but fermentable by gut micro-organisms. | Often referred to as fermentable fibre but can also include oligosaccharides, resistant starch, some amino acids, polyphenols and short chain fatty acids (SCFAs). |

| Synbiotics | Products that combine probiotics and prebiotics. | If the prebiotics feed the probiotic microbes, they’re called synergistic, whereas, if they’re just co-passengers, they’re complementary. In practice, this is often undefined. |

| Probiotics | Live beneficial microorganisms. | Most commonly the bacteria Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium but also non-bacterial microbes such as the yeast, Saccharomyces boulardii. |

| Postbiotics | Dead probiotics and parts thereof. | Common in commercial fermented foods and may also be in probiotic supplements. |

Micro-organisms: our lifelong companions

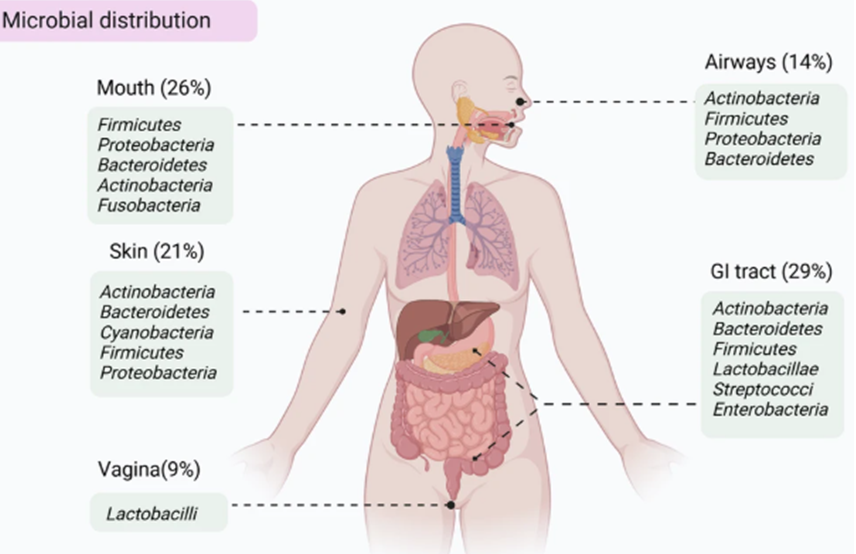

Micro-organisms in the human body aren’t just in the colon, though they are usually found in places which interact with the outside world. See the picture below for some of the places microbiomes can be found. Microbial establishment starts at birth is fairly stable by adolescence. In the absence of disturbances, such as lifestyle and nutrition changes or antibiotics, microbiomes tend to remain fairly unchanged thereafter . (Ref)

Source: Ma et al (2024). (Ref)

According to The Human Microbiome Compendium, a database of colonic gut microbiomes from more than 168,000 people in 68 countries, humans have between 10 and 100 trillion microbes in their colon. While some 2000 species of gut microbes have been identified, an individual usually only has a few hundred, with each species further divisible into strains, your gut microbiome might include 500 - 1000 different strains. (Ref) Microbial diversity is generally lower in people in developed countries and the microbial strains tend to differ to those of people living in less developed countries. This might be due to the latter’s much higher dietary fibre intake; lower exposure to antibiotics; low incidence of caesarean childbirth and higher breast feeding rates; closer proximity to animals and greater exposure to less sanitised environments in general. (Ref)

Microbes: both friends and foes

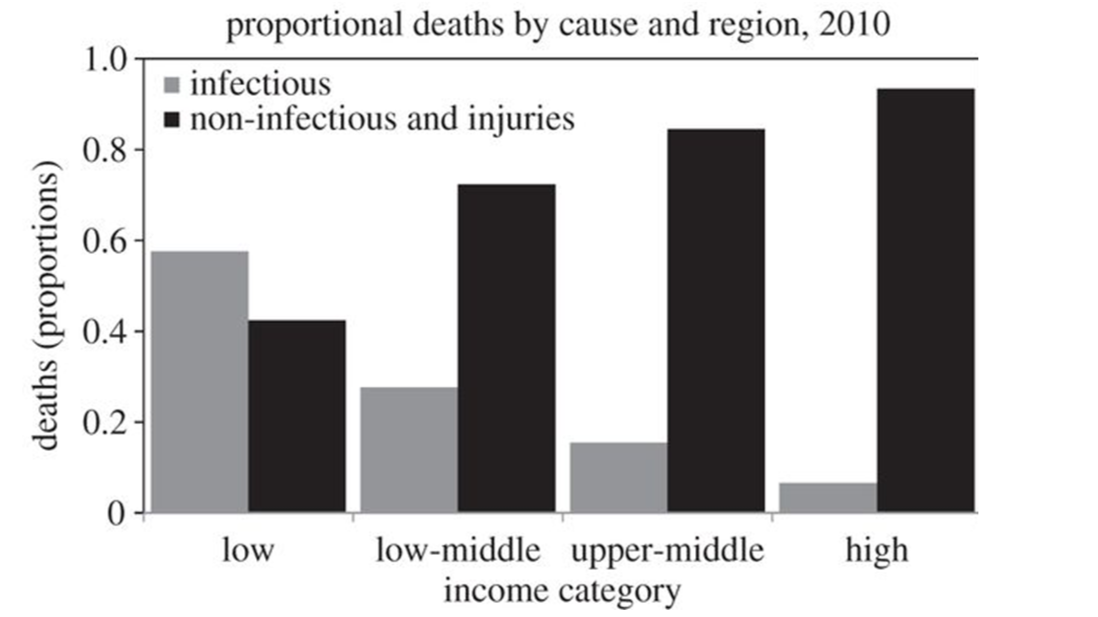

This above pattern is an instance of “what doesn’t kill you making you stronger” - or hormesis if you prefer a more technical term. On the one hand, infectious diarrhoea is still a major cause of death in the developing world, particularly in children, so antibiotics and sanitisation can still be considered a force for good! (Ref) Conversely, a diverse gut microbiome can exert a positive health influence both in the colon and systemically, via the release of microbial chemical messengers into the circulation which activate immune cells throughout the body. One such mediator, butyrate, for example, reduces systemic inflammation and this is hypothesised as a key mechanism for the observed protective effect of some microbes against chronic disease, while dysbiosis (poor gut microbial health), especially after antibiotic administration in early life, is increasingly thought to be behind a steep rise in allergies. (Ref, Ref, Ref, Ref) Support for these hypotheses is often found by comparing healthy comparator individuals’ microbiota to that of a individuals with suspected gut microbial disruption (generally using a faecal sample). For instance, infants with and without antibiotic exposure; ethnic populations in a less developed country of origin, compared to post-migration to a more developed country; and the microbiome of healthy people compared to those with chronic disease.

As deaths due to infectious disease become less common, deaths due to chronic disease tend to rise. Source: World Bank (2010). (Ref)

Nutrition and the gut microbiome

Nutrition is probably they key everyday modifiable factor for the gut microbiota, with a western diet linked to chronic disease, albeit mostly via overnutrition, but also via dysbiosis. (Ref)

Here prebiotics make their entrance, as they are edible compounds but nondigestible by humans. Instead they are fermentable by beneficial resident gut bacteria, which, being well fed, are encouraged to reproduce and produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), namely butyrate, acetate and propionate, which contribute numerous health benefits locally in the gut and systemically throughout the body.

Increased populations of beneficial bacteria (Ref)

Enhanced short chain fatty acid production with benefits throughout the body (Ref)

Improved mineral absorption, especially magnesium and calcium (Ref)

Reduced risk of colon cancer (Ref)

May reduce the symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome (Ref, Ref)

Crowd out pathogenic bacteria (Ref)

For more information on some of the benefits of a healthy gut microbiome, see this article on fibre.

And here’s a list of many of the main types of prebiotics. They are generally, but not always, fermentable carbohydrates (for example polyphenols are not carbohydrates) and, excepting human breast milk, almost always of plant-origin.

| Prebiotic | Sources |

|---|---|

| Fructooligosaccharides (FOS) | Artichoke, onions, leeks, garlic, asparagus, yacon |

| Inulin | Chicory, Jerusalem artichoke |

| Galactooligosaccharides (GOS) | Dairy products, legumes, root vegetables |

| Human milk oligosaccharides (HMO) | Breast milk |

| Lactulose | Manufactured |

| Acacia fibre (Gum arabic) | Plant-derived |

| Xylooligosaccharides (XOS) | Corncobs, sugarcane bagasse |

| Resistant starch | Unripe bananas; cooked and cooled starches |

| B-glucan | Oats and barley |

| Arabinoxylan | Wheat bran, barley bran, rice bran, brewer’s grain |

| Polyphenols | Berries, coffee, cocoa |

Substrate preference and cross-feeding

Now it’s true than the various species of desirable gut microbes have different preferred substrates (food). For instance, guar gum (a common additive in processed food) can increase Akkermansia and Faecalibacterium (Ref); while acacia can increase Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus (and reduce rogue elements such as Escherichia coli and Clostridium) (Ref); while XOS and FOS increase Bifidobacterium and, to a lesser extent, Lactobacillus (Ref, Ref).

But you don’t necessarily need to know all that to encourage a healthy microbiome as the metabolic outputs from one bacterial species in the gut can cross-feed other microbe species resulting in a multiplicative effect. For example, inulin increases butyrate but indirectly. The main bacteria stimulated by inulin, Bifidobacteria, ferments inulin to produce acetate, which then feeds butyrate producing bacteria. (Ref)

Thus, for most people, eating a diversity of plant foods will maximise the chances of adequately nourishing their microbiome.

What about prebiotics and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)?

In people who experience IBS, some foods, particularly the FOS and GOS oligosaccharides (the ‘O’ in FODMAP), trigger enthusiastic colonic microbial fermentation which can cause gut spasm and much gas. It seems that the degree of fermentation is equivalent in both sufferers and non-sufferers, but with IBS, the mucosal nerves are more sensitive to all this colonic turmoil. This is a pity as, of course, fermentation means more SFCAs and more beneficial microbes: the very things we want to encourage! (Ref, Ref) All is not lost. There is evidence that prebiotics with a higher polymerisation (that is a higher number of simple sugars linked in a chain) are fermented more slowly, producing less colonic unrest. Longer chain prebiotics, such as inulin, acacia, XOS and resistant starch, are often better tolerated, perhaps explaining their omnipresence in prebiotic supplements. (Ref, Ref, Ref)

Why prebiotics might not work

The quantity, type and duration of prebiotic ingestion will be germane to your results. Microbes aren’t just for Christmas and need ongoing nurturing including a varied diet of prebiotics if they are to survive. Also, and crucially, a bacterial seeding population must be present in order for it to be able to replicate. (Ref) For instance many Japanese have a gut microbe which can digest a specific algae carbohydrate. Lacking this microbe, no amount of algal feeding will stimulate into existence a microbe which is absent. (Ref) You can probably survive without the prebiotic benefits of red kelp but, more broadly, restoration of a healthy microbiota may require both the addition of missing microbiota (possibly through probiotics or faecal transplantation* (Ref)), as well as establishing conditions conducive to their colonisation, most saliently, feeding them. (Ref)

*Faecal microbial transplant (FMT) is beyond the scope of nutrition but, nevertheless, is a fascinating topic. The Australian Red Cross has received approval to supply FMT for patients with intractable Clostridium difficile infection. Healthy donor stool is collected, tested and processed, then administered via enema or colonoscopy. This is an area of much medical research and FMT may well become a therapeutic option for many more conditions in future. (Ref)

Synbiotics

Synbiotics combine a prebiotic with a probiotic. They may simply act as a mixture of the two, or they may function synergistically: the probiotic feeding on the prebiotic during gastrointestinal transit and enhancing its survival on the long and arduous journey through the chemicals and perturbations of the stomach and small intestine. As it travels, a synergistic synbiotic can release helpful SCFAs; stimulate intestinal immune cells, which in turn to promote bodily immunity; and may even reach and, potentially, colonise the colon.

While ingesting prebiotics to feed resident gut bacteria needn’t be terribly precise, with synergistic synbiotics the prebiotic needs to be a desirable food for its co-travelling probiotic. If you look on the back of the pack of many probiotics in your local chemist, you’ll often see inulin or acacia included in their ingredients as these are generally well tolerated prebiotics.

The bottom line

You don’t need to go and buy special prebiotic supplements (though there are no shortage of people willing to sell them to you). A diet containing a range of plant foods will deliver all the prebiotics you need. However, if you are a consumer of probiotics, you may find that a prebiotic is already included in the mix and this is probably a good thing as it can enhance the probiotic’s effectiveness. Next time, we’ll delve into the world of probiotics and see when and how they can help us.