Postbiotics - the new, new thing in gut health

Introduction

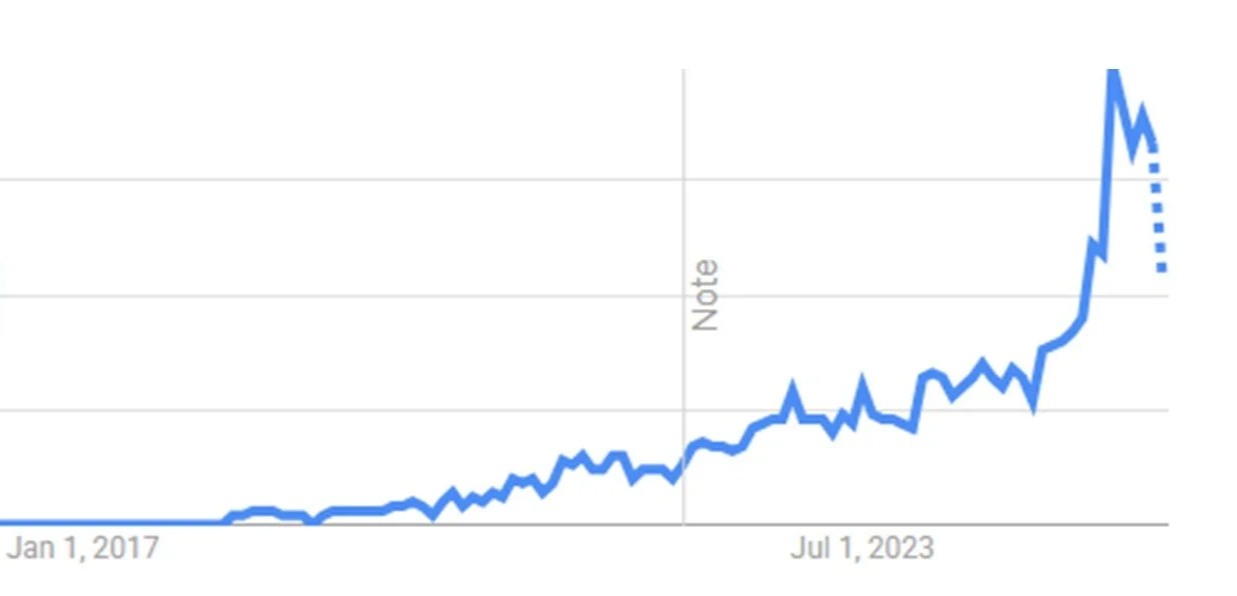

Postbiotics are the latest buzzword in gut health – and possibly beyond. You can see in the Google Trends graph here how it escalated as a search term in 2025.

Source: Google trends. (Ref)

I was going to also write about fermented foods as well in this article, but (what was I thinking?) it would have been way too long, so that’s for next week. The downside is that there’re fewer takeaways today - and I always like to include a takeaway. But I predict postbiotics are going to be a big deal and they’re also a useful stepping stone into fermented foods.

Why the buzz? For one, they make life easier for manufacturers, so they will doubtless be pushing them into your consciousness, but the science has some basis and postbiotics also broaden the potential applications of biotics, so we’ll see a lot more of them around for sure. Just like probiotics, there will be a lot of false prophets so it’s well to be across the details.

So far, we’ve looked at prebiotics, synbiotics and postbiotics. These similar names can be confusing so let’s review some definitions.

Prebiotics

Prebiotics (discussed here) are simply food for desirable gut microbes. Well-fed microbes produce helpful molecules (metabolites) and are encouraged to reproduce. Prebiotics are found in many, many foods, almost exclusively plant-based, though are also available as supplements – of course they are. They’re mostly fermentable carbohydrates, a type of fibre, but there are other types too. For instance, human breast milk provides prebiotics for babies.

Probiotics

Probiotics (discussed here) are the “live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host”. (Ref) Most are bacteria but some yeasts and fungi also make the grade. When you’re considering buying a probiotic to address a particular condition, ensure it stands up to scrutiny. Proper probiotics are strain specific. They should be genetically sequenced, replicable and able to survive processing, storage, and passage through the digestive tract. And to really qualify for the name, the health benefits should have been demonstrated in human studies (not just on agar plates or in rats). (Ref)

Synbiotics

Synbiotics (discussed here) are mixtures of probiotics and prebiotics – the latter there to improve probiotic survival as they transit the gastrointestinal tract. (Ref) If you look at the back of the bottle, many probiotics, also contain inulin or acacia, so are actually, in fact, synbiotics.

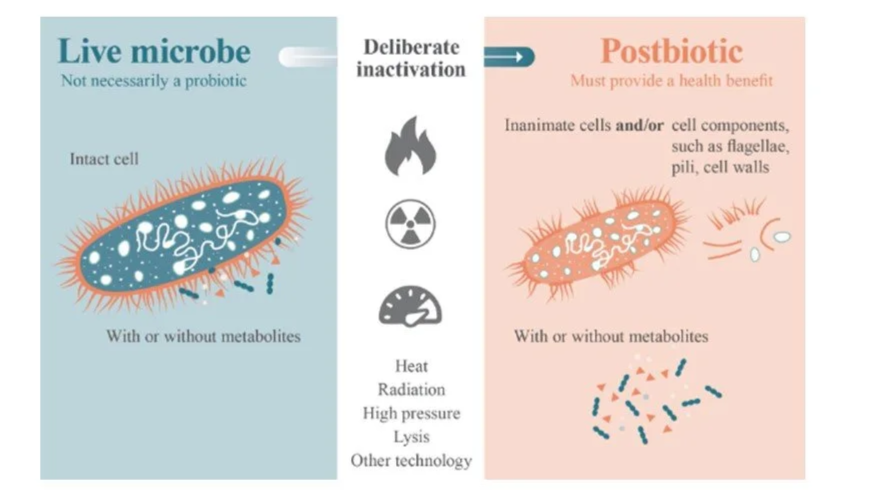

Introducing Postbiotics

The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) defines postbiotics as “a preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host”. (Ref) So intact cells, or cell fragments are a prerequisite, while microbe metabolites are optional and benefits might be derived from any or all of these elements. A postbiotic is not necessarily derived from a probiotic, broadening the field of potentially beneficial microbes.

What are Postbiotics?

Source: Vinderola et al (2024) (Ref)

How can they work if they’re dead?

Remember that the main action of postbiotics is not to take up residence in the gut and establish a new population. It’s more complicated than that.

The idea is that benefits traditionally ascribed to probiotics might be delivered even if the cells are dead to a greater or lesser extent. (Ref) The last article also established that the main benefits of probiotics could be put into four buckets shown in the left column of the table below. The right column outlines how postbiotics might still fulfil many of the same functions. (Ref, Ref, Ref)

| PROBTIOICS | POSTBIOTICS |

|---|---|

| Immune modulation – a fancy way of saying the immune response might be increased or decreased but generally in a helpful direction (ie, fewer allergies and sensitivities but better pathogen resistance | The immune system receptors respond to structures on microbe cell walls, which often persist post inactivation. |

| They crowd out bad microbes by sticking to the gut wall so there’s nowhere for the unwanted pathogens to set up house | Postbiotics can also compete for adhesion sites using molecules on their cell walls which persist after inactivation. For example, Lactobacillus acidophilus postbiotic can increase Helicobacter pylori treatment success as it’s great at adhering to the gut cell walls to the detriment of H. pylori. |

| They produce helpful metabolites, such as short chain fatty acids (SFCAs) which keep, not only the colon healthy, but are absorbed into the blood stream and contribute to systemic metabolic health | While the cells are alive, metabolites are produced and often included in the probiotic post inactivation. |

| They can potentially colonise the gut but this is less common unless the gut is a blank slate and even then your diet has to include sufficient nourishment to keep them alive and breeding. | This is only possible with live cells, so doesn’t happen with postbiotics. |

Standarisation has been a problem until now

In Japan, postbiotics have been available for more than a century and some products include pack health claims, while the concept of the human immune system responding to microbial structures and metabolites, rather than the live microbes themselves has been a research theme for some 25 years. (Ref, Ref) Yet the field has been slow to evolve and this probably lies in divergent views on, first, defining probiotics (now accomplished) and, second, in systematising formulations. (Ref)

Addressing the second issue, postbiotics might be an amalgam of cells, cell fragments and/or cellular metabolites, so standardising their composition by each potentially beneficial component is challenging stuff. At this point, standardisation will likely rely on the base microorganism and the process of treatment and inactivation to ensure replicability, rather than teasing out and quantifying each component. (Ref)

Thus, having resolved these two issues, it becomes easier to produce replicable postbiotics and to test them for clinical benefits.

Advantages

In most, though certainly not all, cases, postbiotics are not as effective as prebiotics. (Ref) But, if we can prove they work, then postbiotics have a couple of major plus points: viability and safety.

Viability

As we discussed with the probiotics article, from the time of manufacture to expiry, live cells in probiotic formulations are dying. Manufacturers typically account for live cell attrition by increasing the dose at batch release, meaning, in order for no less than a true-to-label dose to be delivered up to expiry, each dose is in excess throughout the product’s shelf life. This is more costly for the company; doubtless contracts potential shelf-life; and possibly (though remotely) poses safety concerns in vulnerable populations.

Not only, do manufacturers need to account for shelf-life, but also for losses as the probiotic passes through the gastrointestinal tract. The table below shows an excerpt from the TGA’s stability and quality assessment for one probiotic, Bacillus coagulans MTCC 5260 (a.k.a. Unique IS-2) (one of our old friends from the probiotics article), which has demonstrated efficacy in alleviating the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The TGA’s standard template (partly reproduced in the table below) shows the live cell attrition when they are dried (not the same as inactivation) during manufacture and again losses after the dual bodily assaults of gastric acid and bile acids.

Bacillus coagulans strain MTCC 5260 (Ref)

| Loss on drying | <=5.0% |

|---|---|

| Gastric juice tolerance | >50% survival |

| Bile tolerance | Growth on 1.0% bile salts |

| Antibiotic resistance | Sensitive to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamycin, kanamycin, streptomycin, tetracycline and trimethoprim |

| Viable sport count | >= 300 billion CFU/g |

Data source: Therapeutic Goods Association (TGA) 2021. (Ref)

Now with postbiotics, everything is much simpler: Because they’re already dead, viability becomes irrelevant.

Safety

As part of its safety assessment, the TGA examines each probiotic’s antibiotic sensitivity (see above). With live probiotics able to reproduce, there is always the (remote) risk that a probiotic will go rogue and escape the gut to cause systemic infection. This risk is neutralised with postbiotics, as they have no means to replicate and thus are a safer option for anyone with a compromised immune system. For instance, they have been used for a number of purposes in preterm babies, who are clearly a highly vulnerable group. (Ref, Ref)

Applications

This is very much an emergent area. For now, specific postbiotics generally are only indicated in the same disorders as prebiotics, including IBS, diarrhoea and supporting H. pylori elimination. (Ref)

One example was included in the last article: B. bifidum MIMBb75 is effective in the postbiotic form for IBS management - in fact the postbiotic is more effective than the probiotic. (Ref) Another familiar name has shown early potential in a completely different field: Inactivated, that is, postbiotic, L. rhamnosus GG is a promising candidate as an alopecia treatment. (Ref)

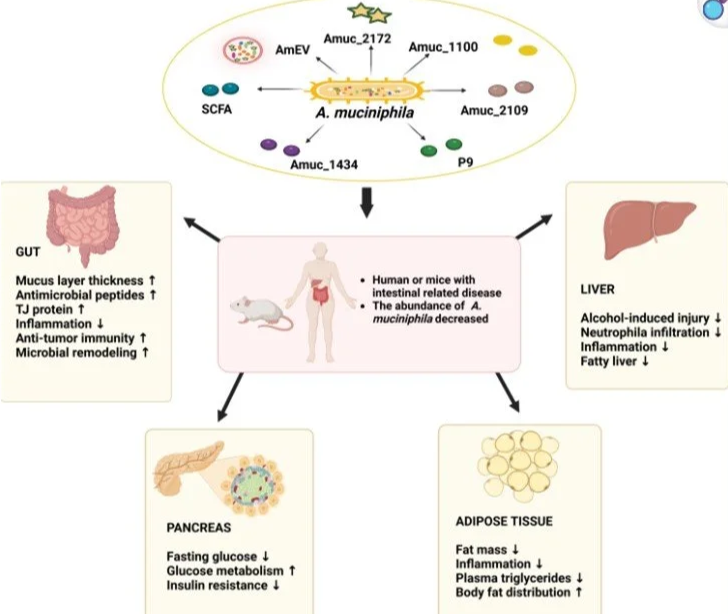

And one that will cross your radar in 2026, if it hasn’t already, is Akkermansia muciniphila. It’s…so hot right now… Although mostly in mice and cell cultures, several strains, probiotic and postbiotic, have demonstrated protective effects against many disorders, including metabolic disease*. (Ref)

Source: Jiang et al (2024). (Ref)

For instance, A. muciniphila can reduce metabolic disease* in mice fed a high fat diet, with the postbiotic more effective than the probiotic for glucose control. (Ref) And in humans? Observational evidence tells us abundant resident gut A. muciniphila is inversely correlated to body weight and metabolic health*. (Ref, Ref) To establish cause and effect: A small 12 week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study gave metabolically unhealthy adults either 1. placebo, 2. live (probiotic) or 3. pasteurised (postbiotic) A. muciniphila. Both versions of A. muciniphila showed a trend for improvement, with postbiotic A. muciniphila generally superior, especially for reducing insulin resistance, but also for cholesterol, liver enzymes and body weight. (Ref)

*Metabolic health can be assessed with several indicators, which tend to trend together. They include cholesterol, blood glucose, blood pressure and body weight, particularly waist circumference.

But before deciding you absolutely must get yourself some postbiotic A. muciniphila, note that this was just a small exploratory study and the results were also fairly immaterial. Moreover, probiotic, rather than postbiotic, A. muciniphila seems to colonise the gut, a much sought after and apparently rare attribute in a probiotic and something we know the postbiotic version cannot do. (Ref) Finally, another study suggested improvements are really only observed where baseline gut A. muciniphila is low at the outset. (Ref)

Still keen? There is one TGA Listed postbiotic A. muciniphila (there’s no probiotic), Flora Reshape - Akkermansia – Theronomic. It actually contains a probiotic and a probiotic as well but we’ll accept that for now. It includes strains and colony forming units and they even cite the science. So far so good. But I couldn’t find the research when I looked for the citations. At this stage, I lost interest and for $126.65 per month, decided I’d go the prebiotic route and eat some pomegranates instead (I’m off wine after this one).

Pomegranates? Red wine? Yes, prebiotics are a good option.

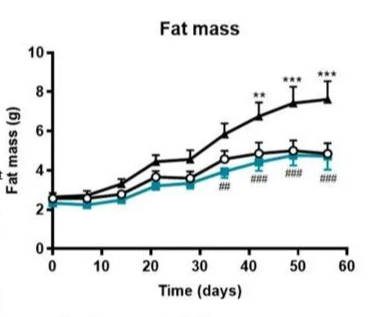

In mice rhubarb produced an abundance of A. muciniphila and was protective against metabolic disease as shown in the charts below. (Ref) While, in people, pomegranate extract*, resveratrol (red wine)*, polydextrose (a food additive that can replace fat and sugar), yeast fermentate (a probiotic but also presumably in yeast products in inactivated form), sodium butyrate (a salt form of butyric acid in garlic, onions, and resistant starch), and inulin (same as sodium butyrate) increased the abundance of A. muciniphila. (Ref)

*As rhubarb is abundant in the polyphenol anthocyanin, as are pomegranate and red wine perhaps this is the common factor - we know from this article that polyphenols can sometimes be prebiotic too. (Ref, Ref)

Mice fed a high fat diet with rhubarb extract (in blue) gained no more weight than control mice (open circles). While those fed a high fat diet without rhubarb (black triangles) rapidly gained weight.

Source: Regnier at al (2020)

Conclusion

This is all very interesting but I appreciate it’s all theoretical for now. Next week we’ll tackle fermented foods, which aren’t probiotics or postbiotics in the strict sense but have many of the same benefits and quite a few more besides. So hold tight to your scobie and we’ll regroup next week.